More Information about folk instruments and their history

The following article is taken from my book,

Blue Smoke Risin' on the Mountain --

a beginner's guide to the mountain dulcimer, 2d edition

copyright 2008 Lee Cagle

The mountain dulcimer is a beautiful instrument, both visually and in its sound. Although its roots lie in the Appalachian Mountain region of the United States, it has captured the fascination of musicians across the globe.

When the United States began to be settled by Europeans, the adventurers and pioneers brought their musical instruments with them from across the ocean. Can you imagine how important music must have been to these people for them to bring their instruments on the long, grueling ocean voyage, where space and possessions were very limited?

When the United States began to be settled by Europeans, the adventurers and pioneers brought their musical instruments with them from across the ocean. Can you imagine how important music must have been to these people for them to bring their instruments on the long, grueling ocean voyage, where space and possessions were very limited?

When bringing the instrument was not possible, they brought the memory of their European instruments and built instruments after arriving in the New World, using native woods and materials.

These courageous and musically stubborn forebearers brought fiddles, guitars, pianofortes, lutes, horn, accordians. And for all of the American ingenuity to which we lay claim, there are few instruments that we can claim as our own.

Based on African gourd instruments, African-Americans gave us the banjo which was used in the minstrel shows of the 1800s. That gift has become the backbone of bluegrass music and the Dixieland sound.

In an effort to reach the masses, the autoharp was produced and sold through the Sears & Roebuck catalogue. This instrument allowed even the most inexperienced player to join in by pressing buttons to make chords while strumming across the strings.

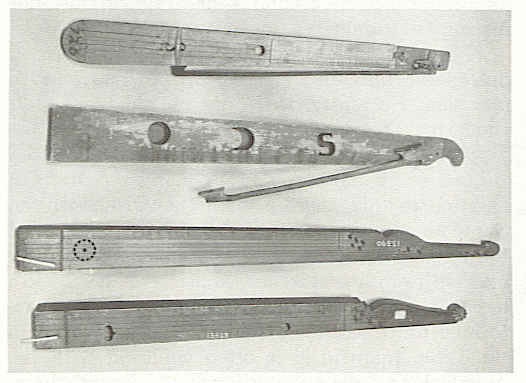

And the mountain dulcimer! No one knows the person who managed to develop the dulcimer in its current form. The mountain dulcimer combines features similar to the fretted zither, the German scheitholt, the Norwegian langeleik and Swedish hummel into the instrument that we play and love today. I am daily amazed at the thought and foresight in the design of this instrument.

The dulcimer has been known by many names including Appalachian dulcimer, lap dulcimer, mountain dulcimer, dulcimore, dulcymore, harmony, harmonium, and hog fiddle. The word

SCHEITHOLTS "dulcimer" comes from the Latin "dulce" which means sweet and the Greek "melos" which means

music. Some also theorize that people were not allowed to be associated with instruments that

were not mentioned in the Bible, so it was a way to have their music without angering the local

preacher. (Remember, the fiddle was called the Devil’s box because it was considered a sin

to play.)1

Traditionally, the mountain dulcimer was played only on the melody string. Therefore, the frets were partial frets placed under the melody string only and did not extend across the fretboard as they do today. The player many times used a wooden stick called a "noter" to fret. Also, prior to the widespread use of plastic picks, the dulcimer was often strummed with a turkey or goose feather. The bass and middle strings were not fretted. They were tuned to harmony notes and acted as drones behind the melody.

There have been many updates in the design of the dulcimer over the years. Shapes have changed from boxes to hourglass and teardrop shapes. Picks have replaced feathers. Frets now extend across the fretboard. Fingers have replaced wooden noters, and chording, rather than melody only, has become commonplace. Also, early dulcimers did not have a 6 ½ fret which was not added until the 1970s. The addition of this fret allows today’s players to play two different scales — the Ionian

HUMMEL scale and the Mixolydian scale — without re-tuning.

Because many of the settlers of the early frontier (western Carolina and eastern Tennessee) were of English and Scots-Irish descent, many of the songs that we consider traditional mountain dulcimer songs are rooted in the English and Celtic tradition. The design of the dulcimer with its droning strings is reminiscent of the sounds of the bagpipe.

Because it uses an open tuning, meaning that the strings harmonize even when no frets are being played, the mountain dulcimer is referred to as a "modal" instrument. The mountain dulcimer is not chromatic, i.e., it does not have all of the notes like a piano. For that reason, the dulcimer may have to be re-tuned in order to achieve certain sounds or to provide the player with desired notes or scales. Those scales, with notes that are flatted or sharped at points outside of the standard major scale, are the "modal scales." Each modal scale is named for one of the seven modes of ancient Greece. Modes will be discussed more fully in the section on Modes and How

LANGELEIK They Apply to the Mountain Dulcimer.

Folklorists and missionaries who traveled to the Appalachian region in the 1800s made

note of the dulcimer in their journals and writings, but some remarked that it was or

soon would be extinct. They were SO wrong!

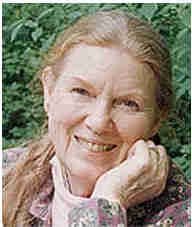

Jean Ritchie was born December 8, 1922, in Viper, Kentucky. Her family history is

rooted in the folk music and ballads of the Appalachian mountains. During her college

career and afterwards, she traveled and took with her the family dulcimer and her

collection of folk songs. After marrying George Pickow and moving to New York, she

continued to educate the public about dulcimer and folk music. The time was right for

the dulcimer to take on a major part in the folk music movement of the 1950s and

1960s. Since that time, the building and playing of dulcimers has grown to almost

every corner of the globe.

1. The instrument that is named in the Bible is not the mountain dulcimer. You may know that there is another

instrument that is also called a dulcimer, but it is the hammered dulcimer. This instrument has its origins in the

region around Persia and it the instrument mentioned in the Bible at Daniel 3:5 (KJV). But no matter the name,

the sound is the same: sweet music.

Resources: The books and writings of Jean Ritchie; Appalachian Dulcimer Traditions by Ralph Lee Smith; The Spirit of the

Mountains by Emma Bell Miles; Jane Hicks Gentry by Betty Smith; the works and collections of Olive Dame

Campbell and Cecil Sharp.

Hammered Dulcimer (portions taken from www.hobgoblin-usa.com)

The hammered dulcimer is a large, many-stringed instrument that is played by hitting the strings with hammers. It is believed ot have originated in the mid-eastern region of the world before Biblical times. The name "dulcimer" is mentioned in the Bible in Daniel 3:5 (KJV). Similar instruments are found in other cultures such as China. It also has a strong history in the English and Celtic traditions.

The Hammered Dulcimer is a diatonic instrument, and the scales available go round the circle of 5ths. The diatonic scale is played by hitting the first 4 strings on the bass side, then switching to the first 4 on the treble side for the next 4 notes of the scale. If the lowest scale is A starting with the first course, then the D scale will start on the 4th course (the 4th note of the A scale), again using the first 4 notes on the bass (right) then switching to the treble (left) side. And so on with the scale of G, C and maybe even F.

The range of the dulcimer is up to 3 octaves usually from D to D''' on a 29 course instrument. This gives the diatonic keys of A, D, G and C.

Bowed Psaltery (portions taken from www.hobgoblin-usa.com and www.stapletonwoodcrafts.com)

The history of the bowed psaltery is unclear. Some music historians claim the instrument dates back to the Hellenistic or Renaissance periods. Others claim it dates back to Biblical times. Although the instrument does appear to be something characteristic of the Renaissance the most generally accepted theories place the origin of the bowed psaltery during the late 1800s or early 1900s. Its design is often credited to a German music teacher who used it as a simple instrument for beginning music students to learn.

It has been suggested that the psaltery, like the lute, came to the courts of Europe with Crusaders returning from the Holy Land. A comparison between European Psalteries and Persian Santirs or Arabian Kanums reveals a likely connection. Although this explanation seems to be well founded and the most widely accepted, two other possibilities exist. The psaltery was well known in Classical Greece and could easily have been brought to Europe by the conquering Romans along with the many other items of Greek culture which they avidly acquired. Earlier still, the Phoenicians traded all over the Mediterranean and along the Atlantic and North Sea coastlines of Europe. It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that psalteries were amongst the items traded by the Phoenicians for Cornish tin.

Psalteries declined in popularity as court instruments in the later Middle Ages in favour of virginals and spinets. Like many other medieval instruments, however, the psaltery did not die out, but continued as a folk instrument passed down, in some versions completely unaltered to the present time.

Bowed Psalteries are triangular in shape with the stings arranged in a manner that permits each string to be bowed separately thus creating the individual notes of a melody. A form of the zither, the strings run from pegs at the base of the instrument to pegs arranged along the side. Set up much like a piano, the notes on the right side of the instrument are tuned like the white keys and those on the left side, the sharps and flats, are tuned like the black keys. Unlike a violin, each string of the bowed psaltery is tuned to a different note so one does not need to finger or fret the strings when playing. Notes played on the bowed psaltery continue to ring after being played, giving this instrument a very haunting and distinctive sound. Most bowed psalteries have 24 strings and a two octave range. The bow is usually made with horse hair and rosined to create sound when it is pulled or pushed over the stings.

Autoharp (portions taken from www.hobgoblin-usa.com)

The name "autoharp" is a trademark of the Oscar Schmidt Company. Other instruments by other manufacturers look and operate in the same manner, but only instruments manufactured by Oscar Schmidt Company can carry the name "autoharp."

The autoharp is based on the fretless zither which is discussed below. Oscar Schmidt and Frederick Menzenhaur who patented the fretless zither were business partners.

The autoharp has strings similar to the fretless zither, but includes bars with pads that damp certain strings to form chords on the strings that are unmuted. The buttons on the bars are labeled with the chord names so that the player can easily see which buttons to push to produce a particular chord. It is usually strummed but can also be plucked.

The autoharp made playing easy and was sold through the Sears and Roebuck catalog. Its simplicity, ready availability and low cost made it a popular instrument among country people in the early 1900s.

The Oscar Schmidt Company continues today as one of the most popular builders of the autoharp.

Strings for the autoharp are very expensive. The reason is that they are only available in expensive sets. All of the wound strings have an unwound bit at each end, so standard strings cannot be used to replace them since they must be specially made. The unwound strings, however, can be replaced with guitar strings of the correct gauge.

Fretless Zither (from Kelly Williams, www.fretlesszithers.net)

Friederich Menzenhauer was the father of the guitar-zither in the United States. He was granted the first patent, whose date is shown on instruments made by various manufacturers. Menzenhauer was born in Magdeburg Germany on January 3, 1858, and traveled to the U.S. on the ship Hohenstauffern from Bremen, arriving in New York on May 8, 1882.

By 1887 he was living in Jersey City, NJ, and was known as a maker of musical instruments. His first patent was issued that year for a "Tremolo Attachment for Cornets," a wind-up device which oscillated a valve in the tube of the horn. His next patent was issued soon after with a similar title, but was a bit more like a "whammy bar" in execution.

In 1892 he married Wilhelmina Geibel, who was born in New York in 1860.

The period of zither development came after 1860. The widely-cited first guitar-zither patent was issued on May 29, 1894. In September, 1895, he received a patent for a "Metallophone Zither", which had chord groups for accompaniment, but played the melody on xylophone bars. At the end of 1896, the Menzenhauer Guitar Zither Co. leased a two-story tin-roofed building in Jersey City. In January 1897, he received a patent for a "Harp Cithern," an odd combination of harp and guitar-zither.

Their only child, Theodore, was born in June, 1897.

In October of 1897, he and Oscar Schmidt were doing business as the U.S. Guitar-Zither Co., which may have been a distributing arm of their organization.

By 1898, he was also doing business as the Menzenhauer Guitar-Zither Co., and the operation was located on Ferry Street in Jersey City, the site of Oscar Schmidt International until 1972. Much of this factory building was in place in 1895, but it is unclear exactly when Menzenhauer obtained this property. Early on, the location was known as 34-41 Ferry Street, the numbers of the lots on the survey of land by the Holland Co. By 1902 the location had received the street addresses 87-101, which the townhouses on those lots still hold today.

In September 1899, he received the first two patents describing what became known as the mandolin-guitar-zither. The next patent, dated June 1900, for an attachment to this instrument, was assigned to Menzenhauer & Schmidt, which was the name of the business around 1900-1901.

At this point, there appears to have been some problem between the partners. On May 7, 1900, Menzenhauer transferred the Ferry Street property to Oscar Schmidt for $1. And then he disappeared from the Jersey City directory until 1904.

In 1904, he had moved into the house at 22 Sherman Place, where he spent the rest of his life. He was still tinkering with musical instruments, and he started receiving patents again. In 1910, the patent was for a modification of the Mandolin-guitar-zither which used a small key mechanism. In 1911 he patented a playing action which used keys similar in appearance to piano keys. In 1914 he received a patent for a melody-playing action that was eerily reminiscent of the Celestaphone, but with the hammers reversed. His final patent was issued in 1917, for a chord-playing mechanism that allowed separation between the bass string and the remaining three strings of the chord.

Menzenhauer was apparently more of an engineer than a businessman. His penchant for tinkering continued. In 1918 he was involved with the ice company, and he developed a scheme to remove impurities from the center of ice blocks.

Frederick Menzenhauer passed away on March 1, 1937, leaving a widow, son, and grandson.

Manufacturers Advertising Company was an alias that was used for many years by the Oscar Schmidt-International Corp. The address was always the same as the actual company.